Reflections on a Year (and some) of Pandemic Teaching

It’s been more than a year since I last posted on here about teaching and which pedagogical strategies and activities I’ve found most useful and well received by my students. After a year of teaching from our homes and staring into the sometimes very dark abyss of black Zoom squares, I think we’ve all learned some valuable lessons, but there are also many things we will be glad to leave behind. After decompressing a bit from the Spring semester and looking at my student evaluations (as problematic as these are—I do value the comments), I thought it might be worthwhile to reflect on what I found could work in the future, back-to-campus semester. I’ve also taught at two different institutions during this time—going from teaching as a contingent faculty member in a Classics Department (at Georgetown) to a tenure-track faculty member in a History Department and on a campus which has no Classics Department (or program). Where I am now, there is no Latin or Greek outside of independent studies. So this is a campus which represents in many ways the inevitable “Post-Classics Future” (as I call it) that many campuses may encounter in the years and decades to come (more on that in another post, coming soon!).

So while there’s so much I could write about, like last time, I’m going to limit myself to four takeaways from this past year of pandemic teaching:

Road Testing a New Course:

Migration and Mobility in the Roman Empire

For Spring 2020, and as part of a grant I received for diversity enhancement of the curriculum from the Doyle Seminar Program, I created a new course from scratch on migration and mobility—and many associated issues—in the Roman Empire. The Doyle Seminar allowed me to take students on one (of two, planned) trip to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, along with my colleague Professor Jennifer Boum Make’s French class on Caribbean Xings 20-21st Centuries. You can find an annotated version of the syllabus here. By annotated, I mean a version in which I’ve commented on what worked and crossed out things I didn’t end up getting my students to do or read (or wouldn’t get them to read again), or what I changed due to the pandemic. I’ve also tried to add links to as many of the readings as possible. I think this is something we should all be willing to do and is helpful for colleagues, since no class is perfect and nor is any syllabus (eventually I’ll get around to doing this for my other courses). There are always elements that didn’t work, readings that fell flat or were received in odd ways. So I hope this is of some use to you, dear reader.

Due to the pandemic, some elements of the class went online: Professor Dan-el Padilla Peralta was scheduled to come visit the last class of the semester in person, but of course, this became a virtual visit—no less powerful. This virtual format also allowed me to invite, last minute, to my class a friend and my co-editor in a volume on Displacement and the Humanities, and arguably one of the leading experts on migration and mobility in the Roman world: Professor Elena Isayev—indeed parts of her class on a similar topic informed my own (see below). This proved to be very fruitful too, as we were able to have a dialogue with her about her work on Livy’s speech of Camillus. I hope that we can keep these virtual “guest” visits in years to come.

At the core of the class were two key components which I think “made” the class what it is—in addition to an overarching dialogue in the weekly readings between the “ancient” phenomenon and a more modern or contemporary, possible instantiation of that phenomenon (echoing what we are trying to achieve in the Displacement volume mentioned above):

1) The Collective Dictionary Project:

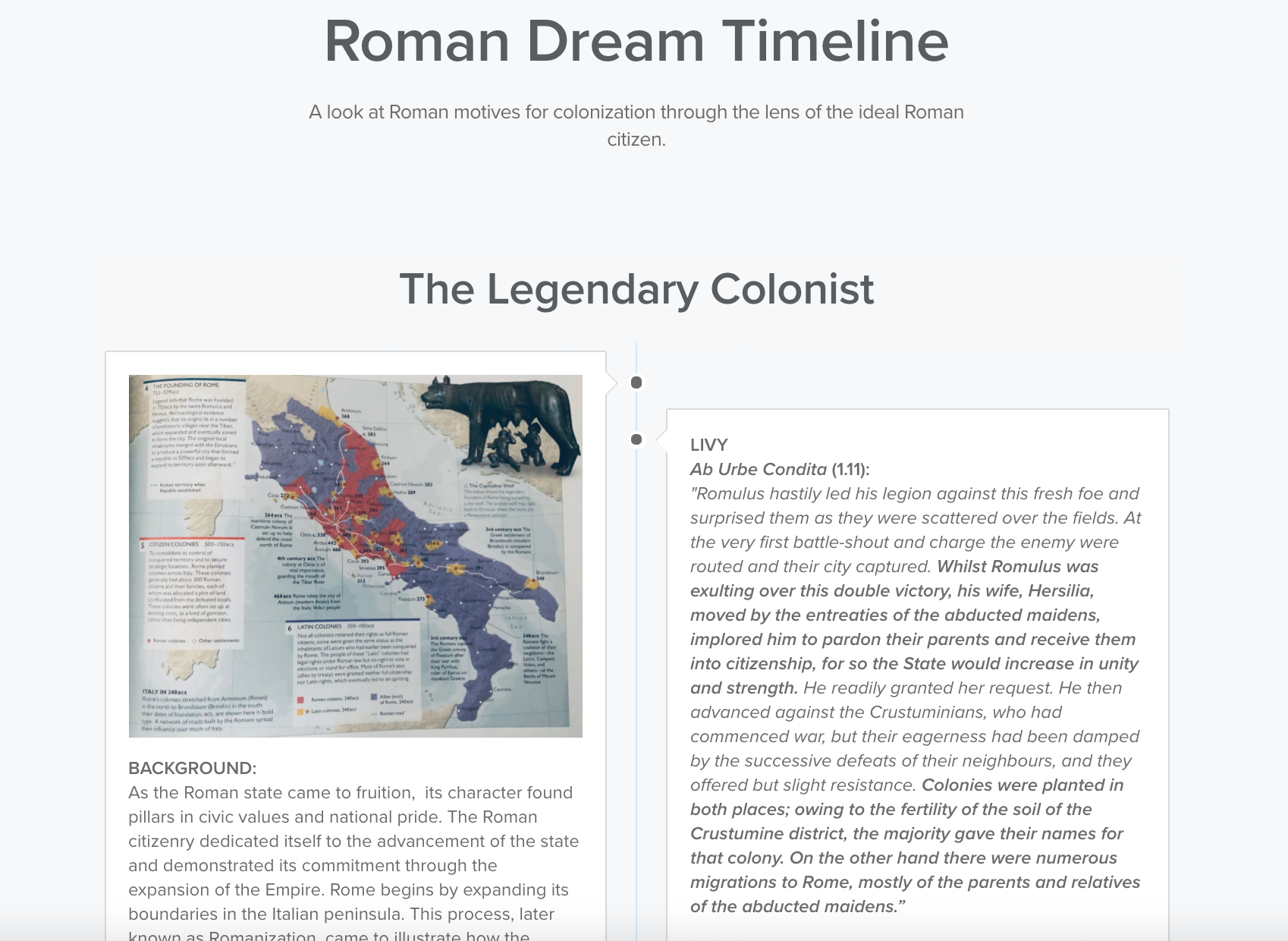

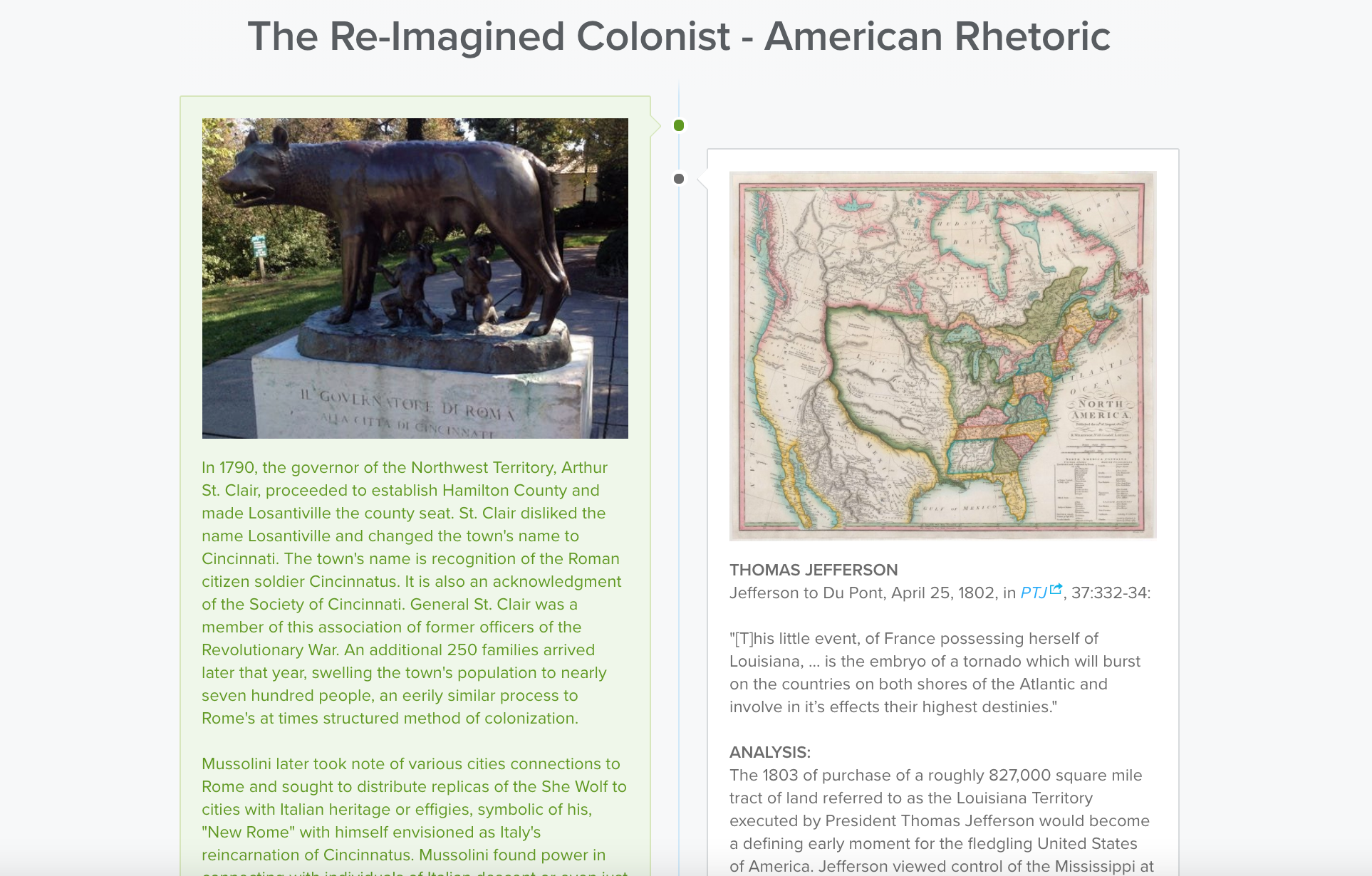

Here I adapted an assignment designed by Professor Elena Isayev. She had her class work with Campus in Camps to produce a “collective dictionary” entry on the word Xenia. My class, through a brainstorming and discussion session, decided on a their own topic which they would produce entries for in groups of 3-4 students: the “Roman Dream”, where they essentially asked: Did an idea similar to the “American Dream”, sometimes sought after or envisioned by (im)migrants to the USA, exist in the ancient Roman world?

How did this go? Well, due to the pandemic, we weren’t able to produce one cohesive collection of entries, and I expanded the medium to allow for videos, timelines and slideshows. One group, which looked at the connection between colonization (Roman and American settler colonization) and the “Roman Dream”, produced a visual and textual timeline using Sutori.

Another group created a YouTube video, including reflections on their own family’s immigrant stories. While I must stress that none of these are “perfect”, I was really impressed by the different directions and media my students chose—and that they managed to do so when the world in a state of huge upheaval. (Note: this was only half of the project, the other half involved each student writing a critical essay on the “Roman Dream”). I imagine that when I next teach a version of this class (expanded to Immigration in the Ancient World for Spring 2022) I will find very different (but also, similar) perspectives among my Rutgers students.

2) Reading Vergil’s Aeneid alongside Dan-el Padilla Peralta’s Undocumented

I took a real risk and decided to pair two books alongside each other, the Aeneid, and Padilla Peralta’s autobiographical account of his own immigration odyssey, Undocumented. My hope was that by reading them together, that Undocumented might throw into stark contrast the so-called “refugee narrative” of Aeneas and the problems inherent with that type of analysis. This couldn’t have been a better choice. My students had to read these texts throughout the semester and write four blog posts comparing them at different pit-stops along the way (we would also discuss different books/chapters from the two texts in class too). This approach threw up new questions, points of similarity and divergence, every time a blog post was due and made me re-think the way I read the Aeneid too. In the final class meetings of the semester, all students had to read each other’s blog posts and we focused first on the Aeneid and then Undocumented and how the experience of one was informed by the reading of the other/Other, and vice versa. We also had the real treat of having Dan-el visit us in our final class where my students got a preview of his work on epistemicide and how the Aeneid is implicated in that Roman project. Thanks, again, Dan-el!

One thing I want to improve in this class: finding accessible, less jargon laden, readings about contemporary displacement and immigration issues. You’ll see in the syllabus that I crossed out a few of these—they were just not that accessible in the end.

Rise of Rome: Podcasting Roman Deaths!

Augustus’ death by Matthew Sawyer, Alison Stabeno, Daniel Rothamel, Oliver Sapon and Giordan Stafford.

Antinous’ death by Marcia Baker, Cassius Blankenship and Stephanie Emmerson.

Inspired by a friend in English (former Prof. Andy Crow at Boston College), who created a podcast assignment for their American Crime Stories class, I decided to adapt their creative task for my Rutgers Rise of Rome class. Similar to a “whodunnit?” premise, I asked my students to create a podcast episode investigating the death of a famous or lesser-known person from Roman history, focusing especially on the source problems surrounding the death and related events, the legacy of their death and its wider historical significance. They had to submit a draft script, complete with footnotes/citations and bibliography, and then a few weeks later, after incorporating my feedback, they presented their final product in our last class for the semester. Some of them took the humorous route (Tarpeia and Augustus), others were more serious (Antinous and Nero), but all in all, again, I was impressed by the high standard of the presentations and the level of research that went into them. I have been given permission by my students below to show case some of the podcasts on the following Roman deaths: Antinous, Augustus, Nero and Tarpeia. (Other deaths covered included Hannibal, the Gracchi brothers, and Cleopatra). I hope you enjoy listening!

Of course, even amidst the amazing fruits of this assignment, there were some lessons learned. While I did encourage my students to interview outside, academic experts for their podcasts—none did end up doing this—I should send out a warning to fellow teachers who might try this assignment out: beware of podcasters who might “volunteer” their services as, say, a narrator. I encountered this unfortunately with one group, whose podcast was dominated by the voice of Spencer Klavan, the host of a right-wing political podcast which offers inaccurate takes on ancient history and antiquity more generally, called Young Heretics. On top of this, as an Oxford educated classicist, he should have known better than to interfere in the class of a colleague—and to advertise his own podcast through a student project (he added his own plug at the end of the podcast).

Things which worked again–and again

If you look back to my teaching roundup from Fall 2019, I can say that certain activities and assignments have been successfully used again, including digital mapping tasks (now a regular part of my take-home exams), using the Georgetown Slavery Archive in a comparative history of slavery exercise (and now I plan on using the Rutgers Scarlet and Black project for which my colleague Prof. Kendra Boyd is a co-editor), and last but not least, the Roman persona semester-long assignment.

What my students told me worked–and what didn’t

I don’t always think student evaluations are a bad thing, at least in terms of the comments section—even though research shows that they are heavily biased against women, LGBTQ+ folk (so, myself included) and people of color. I do walk my students through what a good evaluation is and encourage them to be honest, but constructive—and that’s what I usually receive (but I’m also a white cis man, so that likely shields me from the type of discriminatory criticisms many others receive). The most frequent suggestion for improvement is always: less reading. I did scale back my readings: note I modified the readings here somewhat from the schedule listed and hope to post an annotated version soon to reflect that; visual material was presented in the class lectures), and I will continue to do this next year.

Other pieces of feedback are clearly more down to student preference for more lecture-based classroom (less breakout groups!), or an even more participatory, active-classroom (I love breakout groups!). I try to strike a balance between the two. Anyway, none of these comments were really that new. But students did appreciate a few new things:

Guest virtual lectures (in class or outside of class for extra credit). For instance, I had Professor Kathryn Welch from Sydney and Tyla Cascaes (PhD candidate at University of Queensland) come in to talk to my Cleopatra class on topics such as Shakespeare and his sources, or Caesar and Cleopatra in films from the 1940s-60s. I allowed my Rise of Rome students to attend, too, for extra credit and many showed up and reported how special it felt to have that opportunity to hear from experts—and ones in Australia at that.

Students clearly appreciated the array of assignments and the potential to express their creativity. Multi-modal assessment is something I’ve done for a while and I’m definitely sticking with it.

Course evaluation comment from HIST 380, Rise of Rome, Spring 2021

Students, above all else, appreciated the fact that I got rid of late penalties, and although I had an extension policy, if they asked for further extensions, so long as I had enough time to grade their work and provide real feedback before the submission of grades deadline, then I would grant them that. And it really didn’t become a problem: the students who weren’t ever going to submit the work never did, but for those who really needed it, it made all the difference. Ultimately, it meant that my students were less stressed (and so had better mental health in an already trying time), and so was I.

Course evaluation comment from HIST 380, Rise of Rome, Spring 2021

I’m also going to keep Zoom office hours (held at the same time or a different time to in-person, I haven’t decided)—especially since most of my students commute to campus and work full time jobs, they need that flexibility.